Municipal Challenges, Global Obligations: Urban Childhood Poverty and International Treaty Law

By Kevin Laforest

The intersection of the local with the global has found a new manifestation in Canada’s urban cores. Toronto, where this writer is based, was recently crowned Canada’s child poverty capital. The report released by Campaign 2000, indicated that 28.6% of children in Toronto are living in low-income households. This is down only slightly from 2014’s 29%, a startling 149,000 children. This is not to say this is exclusively Toronto’s, or even Ontario’s concern – urban and childhood poverty can be found across the country. And despite the sheer scope of this problem, Canadians everywhere will have to act quickly as the international spotlight is fast approaching.

This coming spring, the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, (CESCR) the body which oversees the implementation of the ICESCR, will be conducting a review of Canada. The last time the Committee visited was in 2006. Ratified by Canada on 19 May 1976, the International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is o ne of the ten core international human rights treaties.[1]

ne of the ten core international human rights treaties.[1]

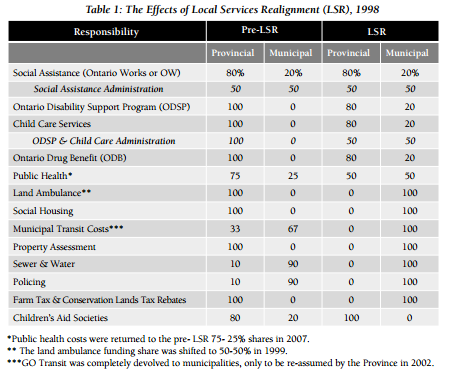

Toronto’s involvement with the ICESCR began in the mid-1990s when local services realignment saw municipalities in Ontario take on a number of new roles as social assistance providers – something that the provincial government had previously been in charge of. The scale of this project can be seen in the table 1, above.[2]

As the city’s social assistance provider for nearly 20 years, Toronto’s response to the current child poverty crisis, entitled TOProsperity, will target six areas of need: housing stability; access to services; transportation; food access; quality jobs and living wages and; institutional change. The intersection of the Committee’s visit and the City’s poverty reduction strategy proves a timely moment to reflect on these obligations, and the different strategies employed to meet them.

There is a tension in the emergence of municipalities as international actors. The Supreme Court in 1994’s Shell Canada Products Ltd. v City of Vancouver which concerned the City’s boycott of Shell’s products due to the latter’s business interests in apartheid South Africa, held that municipalities, “must be restricted to municipal purposes and cannot extend to include the imposition of a boycott based on matters external to the interests of the citizens of the municipality”[3]. The ratio in Shell Canada provides an interesting challenge for municipalities in the increasingly globalized world – global actors with a limited jurisdiction.

This emergence of municipalities onto the global stage provides opportunities for positive change, but remains shrouded in uncertainty. One the one hand, municipalities engaging with issues such as childhood poverty shows great potential for the creation and implementation of bespoke solutions to very local issues. On the other hand, as creatures of statute, cities are limited in the scope of the solutions they may implement. Given this challenge, there is the need for cooperation across provincial and federal and potentially international jurisdictions to engage with the diversity of issues which accompany poverty. This is precisely what international treaties envision.

Downloading the responsibility of urban poverty onto municipalities increases the risk that international treaties become a highly pluralistic regime, subject to localized interpretations of provisions. Nevertheless, TOProsperity and other municipally crafted anti-poverty strategies provide a much more accessible forum for lawyers and concerned citizens alike to ask that all levels of government recognize and respect Canada’s international obligations. TOProsperity, in its closing remarks, declares itself a movement, not a moment[4]. In which direction this movement is going, we have yet to find out.

[1] OHCHR Human Rights Bodies, online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/Pages/HumanRightsBodies.aspx

[2] Andre Cote & Michael Fenn “Provincial-Municipal Relations in Ontario: Approaching an Inflection Point” (2014) 17 Institute on Municipal Finance & Governance, at 10.

[3] Shell Canada Products v Vancouver (City) [1994] 1 SCR 231 at para 101; [1994] 1 RCS 231, [Shell Canada].

[4] City of Toronto TOProsperity, online: City of Toronto <http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2015/ex/bgrd/backgroundfile-81653.pdf>.