Ontario’s Bill

195, “Reopening Ontario (A Flexible Response to COVID-19) Act, 2020”,[1]

which continues the executive’s power to renew emergency measures without

legislative oversight and in the absence of a declared state of emergency, is

inconsistent with international law.

Ontario’s Bill 195,

which came into force on July 23, 2020, (the “Act”) declares the end of the

COVID-19 state of the emergency,while allowing the government to

continue and/or amend emergency measures in force prior to the termination of

the declared emergency. In CLAIHR’s view, this Act is inconsistent with

international human rights law.

Specifically,

the Act:

- revokes

the “declaration of emergency” declared on March 17, 2020; [2]

- grants Cabinet

the power to renew and amend emergency orders that override and/or limit civil

and political rights for 30-days at a time, for up to a year, without the

legislature’s consent or oversight;

- does not

restrict or place any conditions upon Cabinet’s power to renew an order in

accordance with international legal and constitutionally required principles of

necessity, proportionality, and minimal impairment; and,

- enables

the legislative assembly, upon the recommendation of the Premier, to extend Cabinet’s

discretion to renew and amend emergency orders for additional one-year periods indefinitely.

The

emergency measures continued under the Act were enacted in the context of a

declared state of emergency, declared under legislation that limits Cabinet’s

powers to enact emergency measures to those which are “necessary and essential

in the circumstances to prevent, reduce or mitigate serious harm to persons”

(among other stringent criteria).[3] The Act, however, allows

Cabinet to extend such orders even where necessity no longer exists.

COVID-19

has disproportionately impacted racialized and other socioeconomically

disenfranchised groups, accentuating the systemic health and economic

inequities that have led to higher rates of infection, hospitalizations, and

death among marginalized communities.[4] Black peoples, Indigenous

Peoples, brown people, people living with disabilities, migrants, and women are

some of the disproportionately impacted groups, many of whom face multiple and

intersectional forms of discrimination. CLAIHR supports, and will continue to

encourage the government to implement, fair and balanced government measures

aimed at containing the spread of COVID-19 to the extent that these are

consistent with Canada’s international human rights law obligations, which, we

note, are binding on the provinces.[5] In CLAIHR’s view, the Act is inconsistent

with international human rights law governing emergency powers.

In the

context of an emergency, international law permits governments to curtail civil

and political rights only where strictly required by a public emergency

threatening the nation’s survival. However, emergency orders must be legally

prescribed and states of emergency must be limited in duration and scope. Measures

must be the least intrusive to achieve stated public health goals and include

safeguards such as sunset or review clauses. Any extraordinary powers used by

States in an emergency must be transparent. In the absence of a state of

emergency, any restrictions to civil and political rights must be necessary to

the protection of public health, proportional to the threat, minimally

impairing, and non-discriminatory.[6] Such restrictions must be

in accordance with the principles of legality and rule of law. For social and

economic rights, states must continue to respect, protect, and fulfill the core

content of the rights during situations of emergencies.[7]

Unfortunately,

the Act misses the mark. By authorizing the executive, in the absence of

legislative input and oversight, to renew emergency orders without reference to

the principles of necessity, proportionality, and minimal impairment, the Act

allows rights-infringing measures that may have been necessary and

proportionate at the height of the pandemic to be continued where no longer

necessary or minimally impairing, and this in the absence of a definitive

limitation on duration. These failures also

constitute a failure of the democratic process itself, in the absence of public

participation and scrutiny over extensions and proposed amendments.

We note

that among the emergency measures continued by the Act are measures that expand

the police’s power to card and override hard won collective workplace rights

and protections for care workers.[8] Carding disproportionately impacts Black

communities, and Black men, in particular, and care work is disproportionately performed

by women, many of whom are immigrant, migrant, and/or racialized workers.[9] CLAIHR is concerned that

the potentially indefinite continuation of such measures will accentuate the structural

racial discrimination and economic disadvantage experienced by such groups. We remind

the government that international law also protects the right to just and favourable

conditions of work, an adequate standard of living, and physical and mental

health, and prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, sex and gender.[10]

CLAIHR calls

on the Ontario government to amend the Act to comply with the principles of

international law and limit the executive’s authority to renew emergency orders

to circumstances in which renewal is necessary and essential to prevent, reduce

or mitigate the spread of COVID-19. The Act must not be used to illegally and

indefinitely expand unjustifiable and extraordinary State powers. Any extension

of the emergency order must comply with international human rights law

principles of transparency, necessity, proportionality, and be the least

intrusive. No emergency orders can suspend non-derogable rights.[11] In line with these

principles, the government must justify its actions—explaining why the action

is necessary, least intrusive, and proportional.

Further,

CLAIHR calls on the government to amend the Act to clearly limit the

legislative assembly’s authority to extend the executive’s power to renew

and/or amend emergency orders without regular legislative oversight. The Act’s requirement for Ministers or Premier to

report every 30 days is inadequate to determine whether the powers need to

continue, including whether the ‘crisis’ or ‘public health emergency’ still

exists and whether this legislative power continues to be the best tool to use

to respond to emergency. The

government should add a sunset clause or review mechanism to determine whether

the measures need to continue and whether the measures taken are consistent

with human rights principles and the rule of law.

In

conclusion, CLAIHR continues to support measures to curb the spread of

COVID-19. However, this Act provides the

province with broad powers to limit civil and political rights indefinitely and

without democratic participation, in a manner that is inconsistent with

international law. CLAIHR encourages the Ontario government to amend the Act to

ensure its public health protecting measures comply with protect Ontarian’s

human rights and comply with international law.

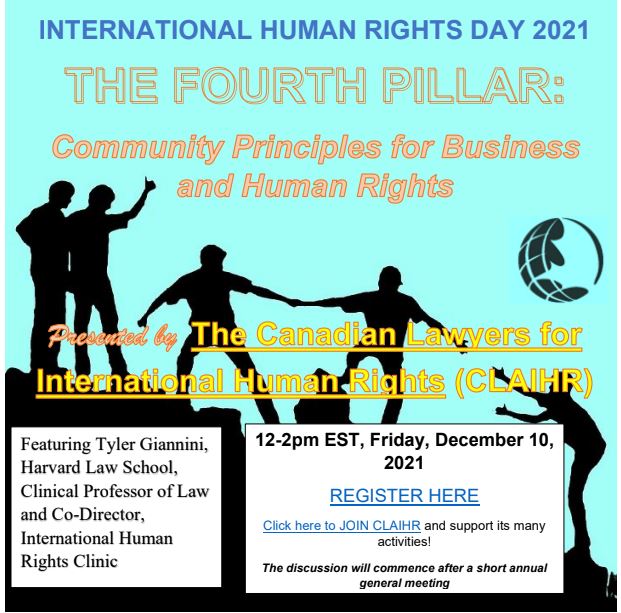

About CLAIHR

CLAIHR

is a non-governmental organization of lawyers, law students, legal academics,

and other jurists, founded in 1992 to promote human rights law from a Canadian

perspective through education, research, and advocacy.

[1] Reopening Ontario (A Flexible Response

to COVID-19) Act, 2020, SO 2020, c 17.

[2] Declaration of Emergency,O. Reg. 50/20, (Mar. 17, 2020). This revocation means that currently there

is no longer a legal state of emergency in Ontario.

[3] Emergency Management and Civil

Protection Act, RSO 1990, c E 9, s 7.0.2(2) (“EMCPA”).

[5]

In accordance with ICCPR, supra note 3 atart. 50.

[6] UN General Assembly, International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 16 December 1966, United Nations,

Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171, art. 4 available at <https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b3aa0.html> (“ICCPR”); UN Human Rights

Committee (HRC), CCPR General Comment No. 29: Article 4: Derogations during

a State of Emergency, 31 August 2001, CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.11, available at

<https://www.refworld.org/docid/453883fd1f.html>; UN Human Rights Office of the High

Commissioner, Emergency Measures and Covid-19: Guidance, 27 April 2020, available at <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Events/EmergencyMeasures_COVID19.pdf>.

[7] UN Human Rights Office of the High

Commissioner, Emergency Measures and Covid-19: Guidance, 27 April 2020, available at <https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Events/EmergencyMeasures_COVID19.pdf>.

[8] Ontario Regulations 114/20, 77/20,

118/20, 157/20, among others.

[9] See Fay Faraday, Canadian Women’s

Foundation, et al, Resetting Normal: Women, Decent Work, and Canada’s

Fractured Care Economy (July 2020), available at <https://canadianwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/ResettingNormal-Women-Decent-Work-and-Care-EN.pdf>.

[10] International Covenant on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights, art. 7;

International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, art. 1,

2, 5; Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

[11] See e.g. ICCPR, s. 4(2) laying

out rights where no derogation is permitted in time of public emergency.