Legal Literacy in the Digital Age

Pictured: the future of legal access?

By Katherine Golobic, JD candidate, University of Toronto

Cody (not her real name) is a PhD student renting a basement apartment in Toronto. She struggles to balance her academic workload with two jobs and endless personal obligations. One evening in early December, her landlord came over to complete some repairs. During the visit, Cody introduced the landlord to her fiancée, Ellen. Cody could immediately tell that the landlord was not comfortable with their relationship, and he left soon after the introduction.

In the weeks that followed, Cody noticed that the landlord became increasingly negligent in his duties – he would wait days before replying to her messages and rarely acknowledged her maintenance requests. Cody is certain that her landlord’s behaviour has changed since his visit in December.

A few weeks ago, Cody’s hot water stopped working. She sent the landlord multiple urgent messages and received only vague replies stating that he was out of the country. The lack of hot water has forced Cody and her fiancée to shower at friends’ homes and at a local gym. Neither Cody nor her fiancée believe they have the resources to find another apartment or access legal help. They were not even aware that a legal remedy for their problem might exist. Feeling overwhelmed and at her landlord’s mercy, Cody wishes that she could access definitive answers and solutions without spending inordinate amounts of money or wasting time in a legal system that she does not trust to begin with.

Legalese, or Legal ease?

Cody’s story (some details have been modified to protect the individuals involved) exemplifies the threats to personal welfare that may arise where individuals lack knowledge about their rights or the availability of legal aid services. According to the Canadian Bar Association (CBA)’s 2013 Reaching Equal Justice Report, over a three-year period of time, 45 per cent of Canadians will experience a legally relevant event. Research has also shown that legal issues tend to “cluster” and disproportionately effect marginalized people (who also tend to be the least well-informed about the justice system).2 For Cody and other vulnerable Canadians, the access to justice crisis is far more complex than merely overcoming economic barriers to legal aid. It lies in a fundamental lack of public legal education. This often manifests itself in distrust of the judicial system, as well as the perception that the law only works for those with a certain degree of social or economic capital. As Cody’s story demonstrates, many people who experience legal problems may even fail to identify them as such. In such cases, lack of knowledge about one’s rights effectively nullifies them.

Research has shown that Canadians tend to view the justice system as untrustworthy, person-dependent, and difficult to navigate. The most commonly cited barriers to access include language, literacy, education, and disability. However, in most circumstances, the absence of basic knowledge of one’s rights is the largest initial hurdle.3 While lack of information is not the sole factor contributing to the realization of legal rights, addressing it may prove to be an efficient and cost effective strategy.

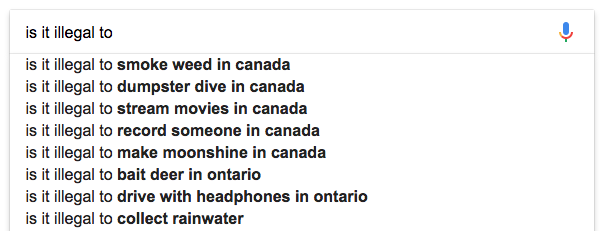

The Digital Future is Now

Comprehensive expansion of public legal knowledge should be as uniform as it is robust, in order to account for the diverse needs of those it serves. Digital technologies and internet platforms are well suited to such a role. According to the Canadian Internet Registration Authority, Canadians are among the top internet users globally, with over 87 per cent of Canadian households having access to online services.4 Mobile and web-based applications have the potential to educate and empower even the most remote citizens at every stage of the legal process. Efforts are currently underway to integrate new technologies into every step of the legal process. The CBA’s 2013 report outlines over thirty distinct targets to be reached between 2020 and 2030,5 including the use of technology in dispute resolution6 and the integration of online legal education into the delivery of services.7

Globally, Canada still trails behind many members of the European Free Trade Association and other developed nations in the accessibility, affordability, and timeliness of its civil justice system.8 While the CBA’s action plan involves harnessing the power of well-established technologies such as the internet, telephone, and audio-visual technology, on the international stage even more innovative projects are underway.

Tech Companies Take the Lead

Private organizations both within and outside Canada are shaping smart phones, cloud computing, and social media into useful tools for citizen engagement with the civil justice system.9 One example is LegalSwipe, a mobile application that provides public legal education and builds community engagement. While the developers concede that only a lawyer can provide legal advice, their goal is to inform citizens of their rights instantaneously and in plain language. The company also operates a not-for-profit called The LegalSwipe Foundation, which offers free legal rights workshops.

Other organizations are challenging ideas of access at even more complex stages of the legal process. The web-based “e-negotiation” application Smartsettle, developed in Vancouver, tackles mediation and dispute resolution, even in cases of multiple parties and/or issues. In the UK, a legal artificial intelligence tool called CaseCrunch is making legal decision predictions with alarming accuracy, exceeding the predictions of lawyers by more than 20 per cent.

Legal Literacy and Digital Literacy: Paths Forward

Ideally, applications such as these will reduce delays through the early management of disputes and help to overcome physical and social isolation from the justice system. However, it remains important to consider inequalities in technological literacy and distribution, as well as ideological backlash from those concerned that technological determinism will become the dominant trend in solving the legal aid crisis.13

These fears are not unwarranted. Many of those who lack access to justice are vulnerable citizens, and saturating the justice system with technological developments could exacerbate its complexity for this population. This demographic also tends to prefer acquiring legal advice from a human.14

Anticipating these issues before they arise and accommodating them will be no easy task, particularly because both traditional and modern approaches face the challenge of ensuring uniformity of information within and across jurisdictions. Nevertheless, a healthy interplay between law and technology can create more opportunities for public participation in the justice system and help to ease the burden of facing such a complicated system in complete isolation.

KG