The Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement: Canada During a Refugee Crisis

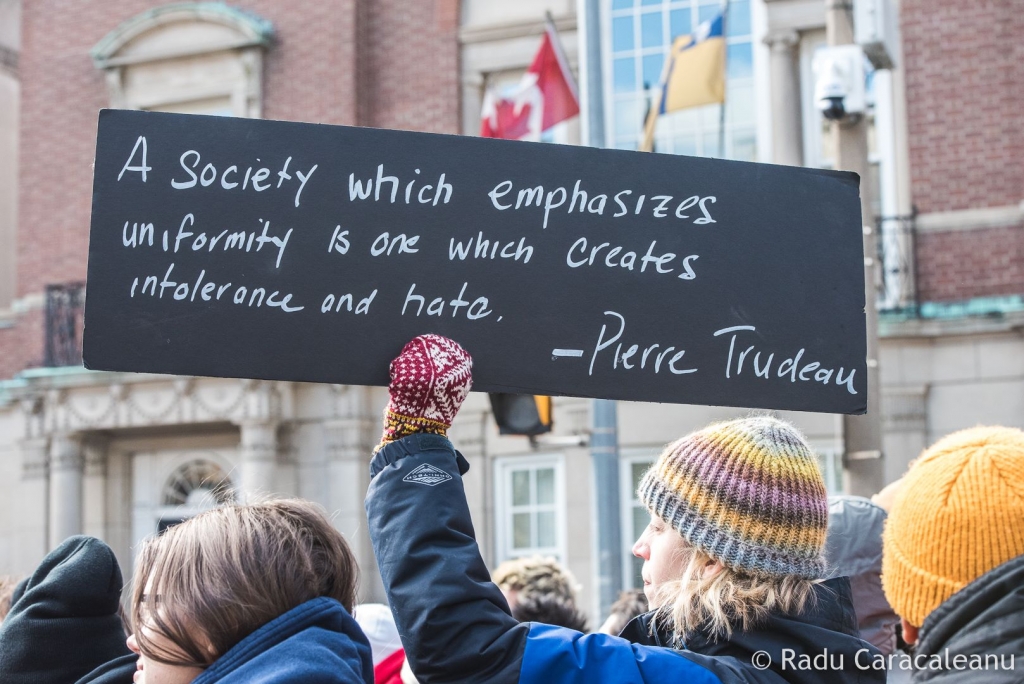

Hundreds of protesters shut down the U.S. Embassy in Toronto on Jan. 30, 2017.

By Jeremy Greenberg

Photography by Radu Caracaleanu

While global outcry over Donald Trump’s refugee ban continues unabated, pressure has been mounting on U.S. allies to take action. For Canada, that has meant the requisite calls to take in more refugees, as well as one proposal that has recently been gaining traction: suspension of the 2004 Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement[1].

What Is the Safe Third Country Agreement ?

Under the Agreement, refugee claimants arriving in the US or Canada are required to register in the first country they arrive in. For example, an individual who landed at JFK Airport in New York would not be permitted to file for refugee status at the Canadian border.

Much like the European Union’s Dublin Regulation[2], the Agreement grew out of a desire to prevent individuals from making refugee claims in multiple countries. The thinking went, if the U.S. and Canada are equally secure, there should be no reason for refugees to traverse one country to settle in the other. That being said, data suggests that the vast majority of these cases now involve claimants coming north. Thus, according to critics, the Agreement is really about preventing people from leaving the United States to make a refugee claim in Canada[3].

What Critics Are Saying

By issuing such a wide-ranging ban on refugees, and indeed whole classes of migrants, critics say that the United States can no longer reasonably be considered a “Safe” country. They argue that the blanket ban contravenes the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as well as the 1984 UN Convention on Torture (by sending people back to places where they are at risk of torture).

Were Canada to rescind or suspend the Safe Third Country Agreement, the argument goes, it would enable those suffering under Trump’s ban to find safe haven north of the border. And as a question of international law, critics believe Canada may be failing its own obligations by refusing to hear the cases of those left in refugee limbo.

The growing chorus of critics ranges from leading civil society actors such as Amnesty International[4] and the Canadian Council for Refugees[5], to legal groups including the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, the Canadian Bar Association, the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers[6] and a national coalition of legal scholars.[7]. Critical editorials have appeared in the Toronto Star[8] and National Post,[9], among other major news sources.

What Canada Is Doing

A day after Trump’s announcement, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau tweeted to the effect that Canada remained open for “those fleeing persecution, terror & war”.[10] Advocates took this as a promising sign, but the government later clarified that no refugee increase was planned, and that the Safe Third Country Agreement would not be reviewed.[11]

From a political perspective, that government’s hesitancy to touch the Agreement makes a certain amount of sense. Given the new president’s penchant for retributivist foreign policy, any action could lead to a serious diplomatic falling-out. Moreover, there remains a whole host of issues to be ironed out with the Trump administration that could be at risk if Canada suddenly stripped the US of its “Safe” status – everything from NAFTA renegotiations to the fate of NATO.

What Comes Next

The most immediate effect of the ban is to put a hold on thousands of pending, and in some cases already approved, refugee claims.[12] The Washington Post, for example, recently profiled a number of refugee children who had been on their way to the US for urgent medical treatment, but now find their way blocked.[13] Due to the Agreement, they are unlikely to be considered for emergency relief by Canada.

Meanwhile, at least 10 refugee claimants were recently reported to have crossed into Canada at the Minnesota-Manitoba border[14]. That group includes at least one family who may prove a crucial test case: not only did they arrive in the United States first, but they have a pending refugee claim there. Under strict application of the Safe Third Country rule, their days in Canada may be numbered.

There are also rumblings of a Constitutional challenge, brought forward by a coalition including Amnesty International and the Canadian Council for Refugees, among others. According to Lorne Waldman, a leading immigration lawyer who worked on a previous challenge to the Agreement, such a case is “extremely likely in the near future”.[15]

Indeed, one interesting aspect of this crisis is that it has shone a light on a long-burning controversy, one that culminated in a 2007 Federal Court decision in which the Agreement was deemed unconstitutional.[16] Although that decision was later overturned, the judge at the time ruled that the US was no longer a “safe” country for refugees, and that the Agreement contravened refugees’ Charter rights to life, liberty and security of the person (section 7) and to non-discrimination (section 15).[17]

That was a decade and two presidents ago, and Trump’s order has changed things. With global condemnation mounting, it all sets up a potentially explosive showdown here in Canada, with activists pressuring politicians to legislate a suspension, and the courts once again considering whether the Agreement is legal at all.

A National Day of Action is scheduled for Saturday, February 4.

[1] http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/laws-policy/menu-safethird.asp

[2] http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/refugee-crisis-eu-first-country-rule-change-puts-pressure-on-uk-to-take-more-asylum-seekers-a6822096.html

[3] http://ccrweb.ca/sites/ccrweb.ca/files/static-files/Lesssafe.pdf

[4] https://www.amnesty.ca/news/amnesty-international-canada-must-strip-usa-%E2%80%9Csafe-third-country%E2%80%9D-designation-refugee-claimants

[5] http://ccrweb.ca/en/safe-third-country

[6] http://ccrweb.ca/en/safe-third-country

[7] https://www.osgoode.yorku.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Lettre-Letter.pdf

[8] https://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2017/01/31/trudeau-should-repeal-refugee-agreement-with-us.html

[9] http://news.nationalpost.com/full-comment/terry-glavin-the-very-least-trudeau-could-do-is-get-out-of-the-way-but-he-wont

[10] https://twitter.com/JustinTrudeau/status/825438460265762816

[11] http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/ndp-kwan-trump-travel-ban-1.3959617

[12] http://www.unhcr.org/news/press/2017/1/588f78ee4/unhcr-alarmed-impact-refugee-program-suspension.html

[13] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/trumps-refugee-ban-is-a-matter-of-life-and-death-for-some-like-a-1-year-old-with-cancer/2017/01/30/4c8e4aae-e711-11e6-903d-9b11ed7d8d2a_story.html?utm_term=.5922a3a052c3&tid=a_inl

[14] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/refugee-border-crossing-manitoba-1.3959558

[15] http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/advocates-lawyers-mull-court-challenge-to-canadas-refugee-pact-with-us/article33872082/

[16] http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/safe-third-country-pact-puts-refugees-at-risk-say-critics-1.328590